The Sunrise Silents Library

THE GARDEN OF ALLAH (BOOK III)

By ROBERT HICHENS

CONTENTS

BOOK I. PRELUDEBOOK II. THE VOICE OF PRAYER

BOOK III. THE GARDEN

BOOK IV. THE JOURNEY

BOOK V. THE REVELATION

BOOK VI. THE JOURNEY BACK

CHAPTERS (BOOK III)

CHAPTER XCHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

BOOK III. THE GARDEN

CHAPTER X

It was noon in the desert.

The voice of the Mueddin died away on the minaret, and the golden silence that comes out of the heart of the sun sank down once more softly over everything. Nature seemed unnaturally still in the heat. The slight winds were not at play, and the palms of Beni-Mora stood motionless as palm trees in a dream. The day was like a dream, intense and passionate, yet touched with something unearthly, something almost spiritual. In the cloudless blue of the sky there seemed a magical depth, regions of colour infinitely prolonged. In the vision of the distances, where desert blent with sky, earth surely curving up to meet the downward curving heaven, the dimness was like a voice whispering strange petitions. The ranges of mountains slept in the burning sand, and the light slept in their clefts like the languid in cool places. For there was a glorious languor even in the light, as if the sun were faintly oppressed by the marvel of his power. The clearness of the atmosphere in the remote desert was not obscured, but was impregnated with the mystery that is the wonder child of shadows. The far-off gold that kept it seemed to contain a secret darkness. In the oasis of Beni-Mora men, who had slowly roused themselves to pray, sank down to sleep again in the warm twilight of shrouded gardens or the warm night of windowless rooms.

In the garden of Count Anteoni Larbi's flute was silent.

"It is like noon in a mirage," Domini said softly.

Count Anteoni nodded.

"I feel as if I were looking at myself a long way off," she added. "As if I saw myself as I saw the grey sea and the islands on the way to Sidi-Zerzour. What magic there is here. And I can't get accustomed to it. Each day I wonder at it more and find it more inexplicable. It almost frightens me."

"You could be frightened?"

"Not easily by outside things—it least I hope not."

"But what then?"

"I scarcely know. Sometimes I think all the outside things, which do what are called the violent deeds in life, are tame, and timid, and ridiculously impotent in comparison with the things we can't see, which do the deeds we can't describe."

"In the mirage of this land you begin to see the exterior life as a mirage? You are learning, you are learning."

There was a creeping sound of something that was almost impish in his voice.

"Are you a secret agent?" Domini asked him.

"Of whom, Madame?"

She was silent. She seemed to be considering. He watched her with curiosity in his bright eyes.

"Of the desert," she answered at length, quite seriously.

"A secret agent has always a definite object. What is mine?"

"How can I know? How can I tell what the desert desires?"

"Already you personify it!"

The network of wrinkles showed itself in his brown face as he smiled, surely with triumph.

"I think I did that from the first," she answered gravely. "I know I did."

"And what sort of personage does the desert seem to you?"

"You ask me a great many questions to-day."

"Mirage questions, perhaps. Forgive me. Let us listen to the question —or is it the demand?—of the desert in this noontide hour, the greatest hour of all the twenty-four in such a land as this."

They were silent again, watching the noon, listening to it, feeling it, as they had been silent when the Mueddin's nasal voice rose in the call to prayer.

Count Anteoni stood in the sunshine by the low white parapet of the garden. Domini sat on a low chair in the shadow cast by a great jamelon tree. At her feet was a bush of vivid scarlet geraniums, against which her white linen dress looked curiously blanched. There was a half-drowsy, yet imaginative light in her gipsy eyes, and her motionless figure, her quiet hands, covered with white gloves, lying loosely in her lap, looked attentive and yet languid, as if some spell began to bind her but had not completed its work of stilling all the pulses of life that throbbed within her. And in truth there was a spell upon her, the spell of the golden noon. By turns she gave herself to it consciously, then consciously strove to deny herself to its subtle summons. And each time she tried to withdraw it seemed to her that the spell was a little stronger, her power a little weaker. Then her lips curved in a smile that was neither joyous nor sad, that was perhaps rather part perplexed and part expectant.

After a minute of this silence Count Anteoni drew back from the sun and sat down in a chair beside Domini. He took out his watch.

"Twenty-five minutes," he said, "and my guests will be here."

"Guests!" she said with an accent of surprise.

"I invited the priest to make an even number."

"Oh!"

"You don't dislike him?"

"I like him. I respect him."

"But I'm afraid you aren't pleased?"

Domini looked him straight in the face.

"Why did you invite Father Roubier?" she said.

"Isn't four better than three?"

"You don't want to tell me."

"I am a little malicious. You have divined it, so why should I not acknowledge it? I asked Father Roubier because I wished to see the man of prayer with the man who fled from prayer."

"Mussulman prayer," she said quickly.

"Prayer," he said.

His voice was peculiarly harsh at that moment. It grated like an instrument on a rough surface. Domini knew that secretly he was standing up for the Arab faith, that her last words had seemed to strike against the religion of the people whom he loved with an odd, concealed passion whose fire she began to feel at moments as she grew to know him better.

It was plain from their manner to each other that their former slight acquaintance had moved towards something like a pleasant friendship.

Domini looked as if she were no longer a wonder-stricken sight-seer in this marvellous garden of the sun, but as if she had become familiar with it. Yet her wonder was not gone. It was only different. There was less sheer amazement, more affection in it. As she had said, she had not become accustomed to the magic of Africa. Its strangeness, its contrasts still startled and moved her. But she began to feel as if she belonged to Beni-Mora, as if Beni-Mora would perhaps miss her a little if she went away.

Ten days had passed since the ride to Sidi-Zerzour—days rather like a dream to Domini.

What she had sought in coming to Beni-Mora she was surely finding. Her act was bringing forth its fruit. She had put a gulf, in which rolled the sea, between the land of the old life and the land in which at least the new life was to begin. The completeness of the severance had acted upon her like a blow that does not stun, but wakens. The days went like a dream, but in the dream there was the stir of birth. Her lassitude was permanently gone. There had been no returning after the first hours of excitement. The frost that had numbed her senses had utterly melted away. Who could be frost-bound in this land of fire? She had longed for peace and she was surely finding it, but it was a peace without stagnation. Hope dwelt in it, and expectancy, vague but persistent. As to forgetfulness, sometimes she woke from the dream and was almost dazed, almost ashamed to think how much she was forgetting, and how quickly. Her European life and friends—some of them intimate and close—were like a far-off cloud on the horizon, flying still farther before a steady wind that set from her to it. Soon it would disappear, would be as if it had never been. Now and then, with a sort of fierce obstinacy, she tried to stay the flight she had desired, and desired still. She said to herself, "I will remember. It's contemptible to forget like this. It's weak to be able to." Then she looked at the mountains or the desert, at two Arabs playing the ladies' game under the shadow of a cafe wall, or at a girl in dusty orange filling a goatskin pitcher at a well beneath a palm tree, and she succumbed to the lulling influence, smiling as they smile who hear the gentle ripple of the waters of Lethe.

She heard them perhaps most clearly when she wandered in Count Anteoni's garden. He had made her free of it in their first interview. She had ventured to take him at his word, knowing that if he repented she would divine it. He had made her feel that he had not repented. Sometimes she did not see him as she threaded the sandy alleys between the little rills, hearing the distant song of Larbi's amorous flute, or sat in the dense shade of the trees watching through a window-space of quivering golden leaves the passing of the caravans along the desert tracks. Sometimes a little wreath of ascending smoke, curling above the purple petals of bougainvilleas, or the red cloud of oleanders, told her of his presence, in some retired thinking-place. Oftener he joined her, with an easy politeness that did not conceal his oddity, but clothed it in a pleasant garment, and they talked for a while or stayed for a while in an agreeable silence that each felt to be sympathetic.

Domini thought of him as a new species of man—a hermit of the world. He knew the world and did not hate it. His satire was rarely quite ungentle. He did not strike her as a disappointed man who fled to solitude in bitterness of spirit, but rather as an imaginative man with an unusual feeling for romance, and perhaps a desire for freedom that the normal civilised life restrained too much. He loved thought as many love conversation, silence as some love music. Now and then he said a sad or bitter thing. Sometimes she seemed to be near to something stern. Sometimes she felt as if there were a secret link which connected him with the perfume-seller in his little darkened chamber, with the legions who prayed about the tomb of Sidi-Zerzour. But these moments were rare. As a rule he was whimsical and kind, with the kindness of a good-hearted man who was human even in his detachment from ordinary humanity. His humour was a salt with plenty of savour. His imagination was of a sort which interested and even charmed her.

She felt, too, that she interested him and that he was a man not readily interested in ordinary human beings. He had seen too many and judged too shrewdly and too swiftly to be easily held for very long. She had no ambition to hold him, and had never in her life consciously striven to attract or retain any man, but she was woman enough to find his obvious pleasure in her society agreeable. She thought that her genuine adoration of the garden he had made, of the land in which it was set, had not a little to do with the happy nature of their intercourse. For she felt certain that beneath the light satire of his manner, his often smiling airs of detachment and quiet independence, there was something that could seek almost with passion, that could cling with resolution, that could even love with persistence. And she fancied that he sought in the desert, that he clung to its mystery, that he loved it and the garden he had created in it. Once she had laughingly called him a desert spirit. He had smiled as if with contentment.

They knew little of each other, yet they had become friends in the garden which he never left.

One day she said to him:

"You love the desert. Why do you never go into it?"

"I prefer to watch it," he relied. "When you are in the desert it bewilders you."

She remembered what she had felt during her first ride with Androvsky.

"I believe you are afraid of it," she said challengingly.

"Fear is sometimes the beginning of wisdom," he answered. "But you are without it, I know."

"How do you know?"

"Every day I see you galloping away into the sun."

She thought there was a faint sound of warning—or was it of rebuke— in his voice. It made her feel defiant.

"I think you lose a great deal by not galloping into the sun too," she said.

"But if I don't ride?"

That made her think of Androvsky and his angry resolution. It had not been the resolution of a day. Wearied and stiffened as he had been by the expedition to Sidi-Zerzour, actually injured by his fall—she knew from Batouch that he had been obliged to call in the Beni-Mora doctor to bandage his shoulder—she had been roused at dawn on the day following by his tread on the verandah. She had lain still while it descended the staircase, but then the sharp neighing of a horse had awakened an irresistible curiosity in her. She had got up, wrapped herself in a fur coat and slipped out on to the verandah. The sun was not above the horizon line of the desert, but the darkness of night was melting into a luminous grey. The air was almost cold. The palms looked spectral, even terrible, the empty and silent gardens melancholy and dangerous. It was not an hour for activity, for determination, but for reverie, for apprehension.

Below, a sleepy Arab boy, his hood drawn over his head, held the chestnut horse by the bridle. Androvsky came out from the arcade. He wore a cap pulled down to his eyebrows which changed his appearance, giving him, as seen from above, the look of a groom or stable hand. He stood for a minute and stared at the horse. Then he limped round to the left side and carefully mounted, following out the directions Domini had given him the previous day: to avoid touching the animal with his foot, to have the rein in his fingers before leaving the ground, and to come down in the saddle as lightly as possible. She noted that all her hints were taken with infinite precaution. Once on the horse he tried to sit up straight, but found the effort too great in his weary and bruised condition. He leaned forward over the saddle peak, and rode away in the luminous greyness towards the desert. The horse went quietly, as if affected by the mystery of the still hour. Horse and rider disappeared. The Arab boy wandered off in the direction of the village. But Domini remained looking after Androvsky. She saw nothing but the grim palms and the spectral atmosphere in which the desert lay. Yet she did not move till a red spear was thrust up out of the east towards the last waning star.

He had gone to learn his lesson in the desert.

Three days afterwards she rode with him again. She did not let him know of her presence on the verandah, and he said nothing of his departure in the dawn. He spoke very little and seemed much occupied with his horse, and she saw that he was more than determined—that he was apt at acquiring control of a physical exercise new to him. His great strength stood him in good stead. Only a man hard in the body could have so rapidly recovered from the effects of that first day of defeat and struggle. His absolute reticence about his efforts and the iron will that prompted them pleased Domini. She found them worthy of a man.

She rode with him on three occasions, twice in the oasis through the brown villages, once out into the desert on the caravan road that Batouch had told her led at last to Tombouctou. They did not travel far along it, but Domini knew at once that this route held more fascination for her than the route to Sidi-Zerzour. There was far more sand in this region of the desert. The little humps crowned with the scrub the camels feed on were fewer, so that the flatness of the ground was more definite. Here and there large dunes of golden- coloured sand rose, some straight as city walls, some curved like seats in an amphitheatre, others indented, crenellated like battlements, undulating in beastlike shapes. The distant panorama of desert was unbroken by any visible oasis and powerfully suggested Eternity to Domini.

"When I go out into the desert for my long journey I shall go by this road," she said to Androvsky.

"You are going on a journey?" he said, looking at her as if startled.

"Some day."

"All alone?"

"I suppose I must take a caravan, two or three Arabs, some horses, a tent or two. It's easy to manage. Batouch will arrange it for me."

Androvsky still looked startled, and half angry, she thought.

They had pulled up their horses among the sand dunes. It was near sunset, and the breath of evening was in the sir, making its coolness even more ethereal, more thinly pure than in the daytime. The atmosphere was so clear that when they glanced back they could see the flag fluttering upon the white of the great hotel of Beni-Mora, many kilometres away among the palms; so still that they could hear the bark of a Kabyle off near a nomad's tent pitched in the green land by the water-springs of old Beni-Mora. When they looked in front of them they seemed to see thousands of leagues of flatness, stretching on and on till the pale yellowish brown of it grew darker, merged into a strange blueness, like the blue of a hot mist above a southern lake, then into violet, then into—the thing they could not see, the summoning thing whose voice Domini's imagination heard, like a remote and thrilling echo, whenever she was in the desert.

"I did not know you were going on a journey, Madame," Androvsky said.

"Don't you remember?" she rejoined laughingly, "that I told you on the tower I thought peace must dwell out there. Well, some day I shall set out to find it."

"That seems a long time ago, Madame," he muttered.

Sometimes, when speaking to her, he dropped his voice till she could scarcely hear him, and sounded like a man communing with himself.

A red light from the sinking sun fell upon the dunes. As they rode back over them their horses seemed to be wading through a silent sea of blood. The sky in the west looked like an enormous conflagration, in which tortured things were struggling and lifting twisted arms.

Domini's acquaintance with Androvsky had not progressed as easily and pleasantly as her intercourse with Count Anteoni. She recognised that he was what is called a "difficult man." Now and then, as if under the prompting influence of some secret and violent emotion, he spoke with apparent naturalness, spoke perhaps out of his heart. Each time he did so she noticed that there was something of either doubt or amazement in what he said. She gathered that he was slow to rely, quick to mistrust. She gathered, too, that very many things surprised him, and felt sure that he hid nearly all of them from her, and would—had not his own will sometimes betrayed him—have hidden all. His reserve was as intense as everything about him. There was a fierceness in it that revealed its existence. He always conveyed to her a feeling of strength, physical and mental. Yet he always conveyed, too, a feeling of uneasiness. To a woman of Domini's temperament uneasiness usually implies a public or secret weakness. In Androvsky's she seemed to be aware of passion, as if it were one to dash obstacles aside, to break through doors of iron, to rush out into the open. And then—what then? To tremble at the world before him? At what he had done? She did not know. But she did know that even in his uneasiness there seemed to be fibre, muscle, sinew, nerve—all which goes to make strength, swiftness.

Speech was singularly difficult to him. Silence seemed to be natural, not irksome. After a few words he fell into it and remained in it. And he was less self-conscious in silence than in speech. He seemed, she fancied, to feel himself safer, more a man when he was not speaking. To him the use of words was surely like a yielding.

He had a peculiar faculty of making his presence felt when he was silent, as if directly he ceased from speaking the flame in him was fanned and leaped up at the outside world beyond its bars.

She did not know whether he was a gentleman or not.

If anyone had asked her, before she came to Beni-Mora, whether it would be possible for her to take four solitary rides with a man, to meet him—if only for a few minutes—every day of ten days, to sit opposite to him, and not far from him, at meals during the same space of time, and to be unable to say to herself whether he was or was not a gentleman by birth and education—feeling set aside—she would have answered without hesitation that it would be utterly impossible. Yet so it was. She could not decide. She could not place him. She could not imagine what his parentage, what his youth, his manhood had been. She could not fancy him in any environment—save that golden light, that blue radiance, in which she had first consciously and fully met him face to face. She could not hear him in converse with any set of men or women, or invent, in her mind, what he might be likely to say to them. She could not conceive him bound by any ties of home, or family, mother, sister, wife, child. When she looked at him, thought about him, he presented himself to her alone, like a thing in the air.

Yet he was more male than other men, breathed humanity—of some kind— as fire breathes heat.

The child there was in him almost confused her, made her wonder whether long contact with the world had tarnished her own original simplicity. But she only saw the child in him now and then, and she fancied that it, too, he was anxious to conceal.

This man had certainly a power to rouse feeling in others. She knew it by her own experience. By turns he had made her feel motherly, protecting, curious, constrained, passionate, energetic, timid—yes, almost timid and shy. No other human being had ever, even at moments, thus got the better of her natural audacity, lack of self- consciousness, and inherent, almost boyish, boldness. Nor was she aware what it was in him which sometimes made her uncertain of herself.

She wondered. But he often woke up wonder in her.

Despite their rides, their moments of intercourse in the hotel, on the verandah, she scarcely felt more intimate with him than she had at first. Sometimes indeed she thought that she felt less so, that the moment when the train ran out of the tunnel into the blue country was the moment in which they had been nearest to each other since they trod the verges of each other's lives.

She had never definitely said to herself: "Do I like him or dislike him?"

Now, as she sat with Count Anteoni watching the noon, the half-drowsy, half-imaginative expression had gone out of her face. She looked rather rigid, rather formidable.

Androvsky and Count Anteoni had never met. The Count had seen Androvsky in the distance from his garden more than once, but Androvsky had not seen him. The meeting that was about to take place was due to Domini. She had spoken to Androvsky on several occasions of the romantic beauty of this desert garden.

"It is like a garden of the Arabian Nights," she had said.

He did not look enlightened, and she was moved to ask him abruptly whether he had ever read the famous book. He had not. A doubt came to her whether he had ever even heard of it. She mentioned the fact of Count Anteoni's having made the garden, and spoke of him, sketching lightly his whimsicality, his affection for the Arabs, his love of solitude, and of African life. She also mentioned that he was by birth a Roman.

"But scarcely of the black world I should imagine," she added.

Androvsky said nothing.

"You should go and see the garden," she continued. "Count Anteoni allows visitors to explore it."

"I am sure it must be very beautiful, Madame," he replied, rather coldly, she thought.

He did not say that he would go.

As the garden won upon her, as its enchanted mystery, the airy wonder of its shadowy places, the glory of its trembling golden vistas, the restfulness of its green defiles, the strange, almost unearthly peace that reigned within it embalmed her spirit, as she learned not only to marvel at it, to be entranced by it, but to feel at home in it and love it, she was conscious of a persistent desire that Androvsky should know it too.

Perhaps his dogged determination about the riding had touched her more than she was aware. She often saw before her the bent figure, that looked tired, riding alone into the luminous grey; starting thus early that his act, humble and determined, might not be known by her. He did not know that she had seen him, not only on that morning, but on many subsequent mornings, setting forth to study the new art in the solitude of the still hours. But the fact that she had seen, had watched till horse and rider vanished beyond the palms, had understood why, perhaps moved her to this permanent wish that he could share her pleasure in the garden, know it as she did.

She did not argue with herself about the matter. She only knew that she wished, that presently she meant Androvsky to pass through the white gate and be met on the sand by Smain with his rose.

One day Count Anteoni had asked her whether she had made acquaintance with the man who had fled from prayer.

"Yes," she said. "You know it."

"How?"

"We have ridden to Sidi-Zerzour."

"I am not always by the wall."

"No, but I think you were that day."

"Why do you think so?"

"I am sure you were."

He did not either acknowledge or deny it.

"He has never been to see my garden," he said.

"No."

"He ought to come."

"I have told him so."

"Ah? Is he coming?"

"I don't think so."

"Persuade him to. I have a pride in my garden—oh, you have no idea what a pride! Any neglect of it, any indifference about it rasps me, plays upon the raw nerve each one of us possesses."

He spoke smilingly. She did not know what he was feeling, whether the remote thinker or the imp within him was at work or play.

"I doubt if he is a man to be easily persuaded," she said.

"Perhaps not—persuade him."

After a moment Domini said:

"I wonder whether you recognise that there are obstacles which the human will can't negotiate?"

"I could scarcely live where I do without recognising that the grains of sand are often driven by the wind. But when there is no wind!"

"They lie still?"

"And are the desert. I want to have a strange experience."

"What?"

"A fete in my garden."

"A fantasia?"

"Something far more banal. A lunch party, a dejeuner. Will you honour me?"

"By breakfasting with you? Yes, of course. Thank you."

"And will you bring—the second sun worshipper?"

She looked into the Count's small, shining eyes.

"Monsieur Androvsky?"

"If that is his name. I can send him an invitation, of course. But that's rather formal, and I don't think he is formal."

"On what day do you ask us?"

"Any day—Friday."

"And why do you ask us?"

"I wish to overcome this indifference to my garden. It hurts me, not only in my pride, but in my affections."

The whole thing had been like a sort of serious game. Domini had not said that she would convey the odd invitation; but when she was alone, and thought of the way in which Count Anteoni had said "Persuade him," she knew she would, and she meant Androvsky to accept it. This was an opportunity of seeing him in company with another man, a man of the world, who had read, travelled, thought, and doubtless lived.

She asked him that evening, and saw the red, that came as it comes in a boy's face, mount to his forehead.

"Everybody who comes to Beni-Mora comes to see the garden," she said before he could reply. "Count Anteoni is half angry with you for being an exception."

"But—but, Madame, how can Monsieur the Count know that I am here? I have not seen him."

"He knows there is a second traveller, and he's a hospitable man. Monsieur Androvsky, I want you to come; I want you to see the garden."

"It is very kind of you, Madame."

The reluctance in his voice was extreme. Yet he did not like to say no. While he hesitated, Domini continued:

"You remember when I asked you to ride?"

"Yes, Madame."

"That was new to you. Well, it has given you pleasure, hasn't it?"

"Yes, Madame."

"So will the garden. I want to put another pleasure into your life."

She had begun to speak with the light persuasiveness of a woman of the world—wishing to overcome a man's diffidence or obstinacy, but while she said the words she felt a sudden earnestness rush over her. It went into the voice, and surely smote upon him like a gust of the hot wind that sometimes blows out of the desert.

"I shall come, Madame," he said quickly.

"Friday. I may be in the garden in the morning. I'll meet you at the gate at half-past twelve."

"Friday?" he said.

Already he seemed to be wavering in his acceptance. Domini did not stay with him any longer.

"I'm glad," she said in a finishing tone.

And she went away.

Now Count Anteoni told her that he had invited the priest. She felt vexed, and her face showed that she did. A cloud came down and immediately she looked changed and disquieting. Yet she liked the priest. As she sat in silence her vexation became more profound. She felt certain that if Androvsky had known the priest was coming he would not have accepted the invitation. She wished him to come, yet she wished he had known. He might think that she had known the fact and had concealed it. She did not suppose for a moment that he disliked Father Roubier personally, but he certainly avoided him. He bowed to him in the coffee-room of the hotel, but never spoke to him. Batouch had told her about the episode with Bous-Bous. And she had seen Bous-Bous endeavour to renew the intimacy and repulsed with determination. Androvsky must dislike the priesthood. He might fancy that she, a believing Catholic, had—a number of disagreeable suppositions ran through her mind. She had always been inclined to hate the propagandist since the tragedy in her family. It was a pity Count Anteoni had not indulged his imp in a different fashion. The beauty of the noon seemed spoiled.

"Forgive my malice," Count Anteoni said. "It was really a thing of thistledown. Can it be going to do harm? I can scarcely think so."

"No, no."

She roused herself, with the instinct of a woman who has lived much in the world, to conceal the vexation that, visible, would cause a depression to stand in the natural place of cheerfulness.

"The desert is making me abominably natural," she thought.

At this moment the black figure of Father Roubier came out of the shadows of the trees with Bous-Bous trotting importantly beside it.

"Ah, Father," said Count Anteoni, going to meet him, while Domini got up from her chair, "it is good of you to come out in the sun to eat fish with such a bad parishioner as I am. Your little companion is welcome."

He patted Bous-Bous, who took little notice of him.

"You know Miss Enfilden, I think?" continued the Count.

"Father Roubier and I meet every day," said Domini, smiling.

"Mademoiselle has been good enough to take a kind interest in the humble work of the Church in Beni-Mora," said the priest with the serious simplicity characteristic of him.

He was a sincere man, utterly without pretension, and, as such men often are, quietly at home with anybody of whatever class or creed.

"I must go to the garden gate," Domini said. "Will you excuse me for a moment?"

"To meet Monsieur Androvsky? Let us accompany you if Father Roubier—"

"Please don't trouble. I won't be a minute."

Something in her voice made Count Anteoni at once acquiesce, defying his courteous instinct.

"We will wait for you here," he said.

There was a whimsical plea for forgiveness in his eyes. Domini's did not reject it; they did not answer it. She walked away, and the two men looked after her tall figure with admiration. As she went along the sand paths between the little streams, and came into the deep shade, her vexation seemed to grow darker like the garden ways. For a moment she thought she understood the sensations that must surely sometimes beset a treacherous woman. Yet she was incapable of treachery. Smain was standing dreamily on the great sweep of sand before the villa. She and he were old friends now, and every day he calmly gave her a flower when she came into the garden.

"What time is it, Smain?"

"Nearly half-past twelve, Madame."

"Will you open the door and see if anyone is coming?"

He went towards the great door, and Domini sat down on a bench under the evergreen roof to wait. She had seldom felt more discomposed, and began to reason with herself almost angrily. Even if the presence of the priest was unpleasant to Androvsky, why should she mind? Antagonism to the priesthood was certainly not a mental condition to be fostered, but a prejudice to be broken down. But she had wished— she still wished with ardour—that Androvsky's first visit to the garden should be a happy one, should pass off delightfully. She had a dawning instinct to make things smooth for him. Surely they had been rough in the past, rougher even than for herself. And she wondered for an instant whether he had come to Beni-Mora, as she had come, vaguely seeking for a happiness scarcely embodied in a definite thought.

"There is a gentleman coming, Madame."

It was the soft voice of Smain from the gate. In a moment Androvsky stood before it. Domini saw him framed in the white wood, with a brilliant blue behind him and a narrow glimpse of the watercourse. He was standing still and hesitating.

"Monsieur Androvsky!" she called.

He started, looked across the sand, and stepped into the garden with a sort of reluctant caution that pained her, she scarcely knew why. She got up and went towards him, and they met full in the sunshine.

"I came to be your cicerone."

"Thank you, Madame."

There was the click of wood striking against wood as Smain closed the gate. Androvsky turned quickly and looked behind him. His demeanour was that of a man whose nerves were tormenting him. Domini began to dread telling him of the presence of the priest, and, characteristically, did without hesitation what she feared to do.

"This is the way," she said.

Then, as they turned into the shadow of the trees and began to walk between the rills of water, she added abruptly:

"Father Roubier is here already, so our party is complete."

Androvsky stood still.

"Father Roubier! You did not tell me he was coming."

"I did not know it till five minutes ago."

She stood still too, and looked at him. There was a flaming of distrust in his eyes, his lips were compressed, and his whole body betokened hostility.

"I did not understand. I thought Senor Anteoni would be alone here."

"Father Roubier is a pleasant companion, sincere and simple. Everyone likes him."

"No doubt, Madame. But—the fact is I"—he hesitated, then added, almost with violence—"I do not care for priests."

"I am sorry. Still, for once—for an hour—you can surely——"

She did not finish the sentence. While she was speaking she felt the banality of such phrases spoken to such a man, and suddenly changed tone and manner.

"Monsieur Androvsky," she said, laying one hand on his arm, "I knew you would not like Father Roubier's being here. If I had known he was coming I should have told you in order that you might have kept away if you wished to. But now that you are here—now that Smain has let you in and the Count and Father Roubier must know of it, I am sure you will stay and govern your dislike. You intend to turn back. I see that. Well, I ask you to stay."

She was not thinking of herself, but of him. Instinct told her to teach him the way to conceal his aversion. Retreat would proclaim it.

"For yourself I ask you," she added. "If you go, you tell them what you have told me. You don't wish to do that."

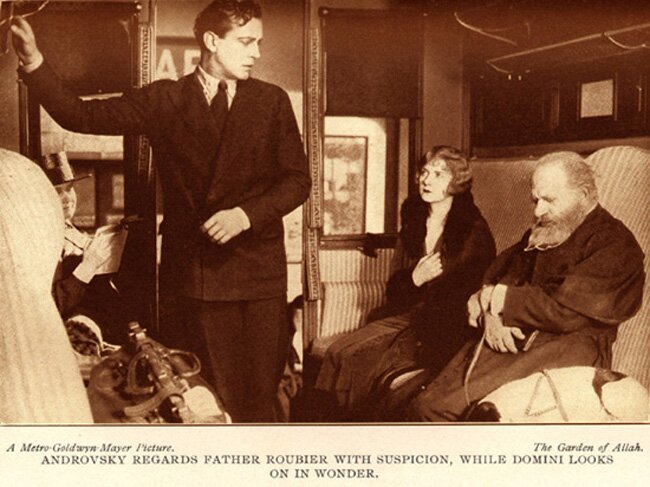

They looked at each other. Then, without a word, he walked on again. As she kept beside him she felt as if in that moment their acquaintanceship had sprung forward, like a thing that had been forcibly restrained and that was now sharply released. They did not speak again till they saw, at the end of an alley, the Count and the priest standing together beneath the jamelon tree. Bous-Bous ran forward barking, and Domini was conscious that Androvsky braced himself up, like a fighter stepping into the arena. Her keen sensitiveness of mind and body was so infected by his secret impetuosity of feeling that it seemed to her as if his encounter with the two men framed in the sunlight were a great event which might be fraught with strange consequences. She almost held her breath as she and Androvsky came down the path and the fierce sunrays reached out to light up their faces.

Count Anteoni stepped forward to greet them.

"Monsieur Androvsky—Count Anteoni," she said.

The hands of the two men met. She saw that Androvsky's was lifted reluctantly.

"Welcome to my garden," Count Anteoni said with his invariable easy courtesy. "Every traveller has to pay his tribute to my domain. I dare to exact that as the oldest European inhabitant of Beni-Mora."

Androvsky said nothing. His eyes were on the priest. The Count noticed it, and added:

"Do you know Father Roubier?"

"We have often seen each other in the hotel," Father Roubier said with his usual straightforward simplicity.

He held out his hand, but Androvsky bowed hastily and awkwardly and did not seem to see it. Domini glanced at Count Anteoni, and surprised a piercing expression in his bright eyes. It died away at once, and he said:

"Let us go to the salle-a-manger. Dejeuner will be ready, Miss Enfilden."

She joined him, concealing her reluctance to leave Androvsky with the priest, and walked beside him down the path, preceded by Bous-Bous.

"Is my fete going to be a failure?" he murmured.

She did not reply. Her heart was full of vexation, almost of bitterness. She felt angry with Count Anteoni, with Androvsky, with herself. She almost felt angry with poor Father Roubier.

"Forgive me! do forgive me!" the Count whispered. "I meant no harm."

She forced herself to smile, but the silence behind them, where the two men were following, oppressed her. If only Androvsky would speak! He had not said one word since they were all together. Suddenly she turned her head and said:

"Did you ever see such palms, Monsieur Androvsky? Aren't they magnificent?"

Her voice was challenging, imperative. It commanded him to rouse himself, to speak, as a touch of the lash commands a horse to quicken his pace. Androvsky raised his head, which had been sunk on his breast as he walked.

"Palms!" he said confusedly.

"Yes, they are wonderful."

"You care for trees?" asked the Count, following Domini's lead and speaking with a definite intention to force a conversation.

"Yes, Monsieur, certainly."

"I have some wonderful fellows here. After dejeuner you must let me show them to you. I spent years in collecting my children and teaching them to live rightly in the desert."

Very naturally, while he spoke, he had joined Androvsky, and now walked on with him, pointing out the different varieties of trees. Domini was conscious of a sense of relief and of a strong feeling of gratitude to their host. Following upon the gratitude came a less pleasant consciousness of Androvsky's lack of good breeding. He was certainly not a man of the world, whatever he might be. To-day, perhaps absurdly, she felt responsible for him, and as if he owed it to her to bear himself bravely and govern his dislikes if they clashed with the feelings of his companions. She longed hotly for him to make a good impression, and, when her eyes met Father Roubier's, was almost moved to ask his pardon for Androvsky's rudeness. But the Father seemed unconscious of it, and began to speak about the splendour of the African vegetation.

"Does not its luxuriance surprise you after England?" he said.

"No," she replied bluntly. "Ever since I have been in Africa I have felt that I was in a land of passionate growth."

"But—the desert?" he replied with a gesture towards the long flats of the Sahara, which were still visible between the trees.

"I should find it there too," she answered. "There, perhaps, most of all."

He looked at her with a gentle wonder. She did not explain that she was no longer thinking of growth in Nature.

The salle-a-manger stood at the end of a broad avenue of palms not far from the villa. Two Arab servants were waiting on each side of the white step that led into an ante-room filled with divans and coffee- tables. Beyond was a lofty apartment with an arched roof, in the centre of which was an oval table laid for breakfast, and decorated with masses of trumpet-shaped scarlet flowers in silver vases. Behind each of the four high-backed chairs stood an Arab motionless as a statue. Evidently the Count's fete was to be attended by a good deal of ceremony. Domini felt sorry, though not for herself. She had been accustomed to ceremony all her life, and noticed it, as a rule, almost as little as the air she breathed. But she feared that to Androvsky it would be novel and unpleasant. As they came into the shady room she saw him glance swiftly at the walls covered with dark Persian hangings, at the servants in their embroidered jackets, wide trousers, and snow-white turbans, at the vivid flowers on the table, then at the tall windows, over which flexible outside blinds, dull green in colour, were drawn; and it seemed to her that he was feeling like a trapped animal, full of a fury of uneasiness. Father Roubier's unconscious serenity in the midst of a luxury to which he was quite unaccustomed emphasised Androvsky's secret agitation, which was no secret to Domini, and which she knew must be obvious to Count Anteoni. She began to wish ardently that she had let Androvsky follow his impulse to go when he heard of Father Roubier's presence.

They sat down. She was on the Count's right hand, with Androvsky opposite to her and Father Roubier on her left. As they took their places she and the Father said a silent grace and made the sign of the Cross, and when she glanced up after doing so she saw Androvsky's hand lifted to his forehead. For a moment she fancied that he had joined in the tiny prayer, and was about to make the sacred sign, but as she looked at him his hand fell heavily to the table. The glasses by his plate jingled.

"I only remembered this morning that this is a jour maigre," said Count Anteoni as they unfolded their napkins. "I am afraid, Father Roubier, you will not be able to do full justice to my chef, Hamdane, although he has thought of you and done his best for you. But I hope Miss Enfilden and—"

"I keep Friday," Domini interrupted quietly.

"Yes? Poor Hamdane!"

He looked in grave despair, but she knew that he was really pleased that she kept the fast day.

"Anyhow," he continued, "I hope that you, Monsieur Androvsky, will be able to join me in testing Hamdane's powers to the full. Or are you too——"

He did not continue, for Androvsky at once said, in a loud and firm voice:

"I keep no fast days."

The words sounded like a defiance flung at the two Catholics, and for a moment Domini thought that Father Roubier was going to treat them as a challenge, for he lifted his head and there was a flash of sudden fire in his eyes. But he only said, turning to the Count:

"I think Mademoiselle and I shall find our little Ramadan a very easy business. I once breakfasted with you on a Friday—two years ago it was, I think—and I have not forgotten the banquet you gave me."

Domini felt as if the priest had snubbed Androvsky, as a saint might snub, without knowing that he did so. She was angry with Androvsky, and yet she was full of pity for him. Why could he not meet courtesy with graciousness? There was something almost inhuman in his demeanour. To-day he had returned to his worst self, to the man who had twice treated her with brutal rudeness.

"Do the Arabs really keep Ramadan strictly?" she asked, looking away from Androvsky.

"Very," said Father Roubier. "Although, of course, I am not in sympathy with their religion, I have often been moved by their adherence to its rules. There is something very grand in the human heart deliberately taking upon itself the yoke of discipline."

"Islam—the very word means the surrender of the human will to the will of God," said Count Anteoni. "That word and its meaning lie like the shadow of a commanding hand on the soul of every Arab, even of the absinthe-drinking renegades one sees here and there who have caught the vices of their conquerors. In the greatest scoundrel that the Prophet's robe covers there is an abiding and acute sense of necessary surrender. The Arabs, at any rate, do not buzz against their Creator, like midges raging at the sun in whose beams they are dancing."

"No," assented the priest. "At least in that respect they are superior to many who call themselves Christians. Their pride is immense, but it never makes itself ridiculous."

"You mean by trying to defy the Divine Will?" said Domini.

"Exactly, Mademoiselle."

She thought of her dead father.

The servants stole round the table, handing various dishes noiselessly. One of them, at this moment, poured red wine into Androvsky's glass. He uttered a low exclamation that sounded like the beginning of a protest hastily checked.

"You prefer white wine?" said Count Anteoni.

"No, thank you, Monsieur."

He lifted the glass to his lips and drained it.

"Are you a judge of wine?" added the Count. "That is made from my own grapes. I have vineyards near Tunis."

"It is excellent," said Androvsky.

Domini noticed that he spoke in a louder voice than usual, as if he were making a determined effort to throw off the uneasiness that evidently oppressed him. He ate heartily, choosing almost ostentatiously dishes in which there was meat. But everything that he did, even this eating of meat, gave her the impression that he was— subtly, how she did not know—defying not only the priest, but himself. Now and then she glanced across at him, and when she did so he was always looking away from her. After praising the wine he had relapsed into silence, and Count Anteoni—she thought moved by a very delicate sense of tact—did not directly address him again just then, but resumed the interrupted conversation about the Arabs, first explaining that the servants understood no French. He discussed them with a minute knowledge that evidently sprang from a very real affection, and presently she could not help alluding to this.

"I think you love the Arabs far more than any Europeans," she said.

He fixed his bright eyes upon her, and she thought that just then they looked brighter than ever before.

"Why?" he asked quietly.

"Do you know the sound that comes into the voice of a lover of children when it speaks of a child?"

"Ah!—the note of a deep indulgence?"

"I hear it in yours whenever you speak of the Arabs."

She spoke half jestingly. For a moment he did not reply. Then he said to the priest:

"You have lived long in Africa, Father. Have not you something of the same feeling towards these children of the sun?"

"Yes, and I have noticed it in our dead Cardinal."

"Cardinal Lavigerie."

Androvsky bent over his plate. He seemed suddenly to withdraw his mind forcibly from this conversation in which he was taking no active part, as if he refused even to listen to it.

"He is your hero, I know," the Count said sympathetically.

"He did a great deal for me."

"And for Africa. And he was wise."

"You mean in some special way?" Domini said.

"Yes. He looked deep enough into the dark souls of the desert men to find out that his success with them must come chiefly through his goodness to their dark bodies. You aren't shocked, Father?"

"No, no. There is truth in that."

But the priest assented rather sadly.

"Mahomet thought too much of the body," he added.

Domini saw the Count compress his lips. Then he turned to Androvsky and said:

"Do you think so, Monsieur?"

It was a definite, a resolute attempt to draw his guest into the conversation. Androvsky could not ignore it. He looked up reluctantly from his plate. His eyes met Domini's, but immediately travelled away from them.

"I doubt——" he said.

He paused, laid his hands on the table, clasping its edge, and continued firmly, even with a sort of hard violence:

"I doubt if most good men, or men who want to be good, think enough about the body, consider it enough. I have thought that. I think it still."

As he finished he stared at the priest, almost menacingly. Then, as if moved by an after-thought, he added:

"As to Mahomet, I know very little about him. But perhaps he obtained his great influence by recognising that the bodies of men are of great importance, of tremendous—tremendous importance."

Domini saw that the interest of Count Anteoni in his guest was suddenly and vitally aroused by what he had just said, perhaps even more by his peculiar way of saying it, as if it were forced from him by some secret, irresistible compulsion. And the Count's interest seemed to take hands with her interest, which had had a much longer existence. Father Roubier, however, broke in with a slightly cold:

"It is a very dangerous thing, I think, to dwell upon the importance of the perishable. One runs the risk of detracting from the much greater importance of the imperishable."

"Yet it's the starved wolves that devour the villages," said Androvsky.

For the first time Domini felt his Russian origin. There was a silence. Father Roubier looked straight before him, but Count Anteoni's eyes were fixed piercingly upon Androvsky. At last he said:

"May I ask, Monsieur, if you are a Russian?"

"My father was. But I have never set foot in Russia."

"The soul that I find in the art, music, literature of your country is, to me, the most interesting soul in Europe," the Count said with a ring of deep earnestness in his grating voice.

Spoken as he spoke it, no compliment could have been more gracious, even moving. But Androvsky only replied abruptly:

"I'm afraid I know nothing of all that."

Domini felt hot with a sort of shame, as at a close friend's public display of ignorance. She began to speak to the Count of Russian music, books, with an enthusiasm that was sincere. For she, too, had found in the soul from the Steppes a meaning and a magic that had taken her soul prisoner. And suddenly, while she talked, she thought of the Desert as the burning brother of the frigid Steppes. Was it the wonder of the eternal flats that had spoken to her inmost heart sometimes in London concert-rooms, in her room at night when she read, forgetting time, which spoke to her now more fiercely under the palms of Africa? At the thought something mystic seemed to stand in her enthusiasm. The mystery of space floated about her. But she did not express her thought. Count Anteoni expressed it for her.

"The Steppes and the Desert are akin, you know," he said. "Despite the opposition of frost and fire."

"Just what I was thinking!" she exclaimed. "That must be why—"

She stopped short.

"Yes?" said the Count.

Both Father Roubier and Androvsky looked at her with expectancy. But she did not continue her sentence, and her failure to do so was covered, or at the least excused, by a diversion that secretly she blessed. At this moment, from the ante-room, there came a sound of African music, both soft and barbarous. First there was only one reiterated liquid note, clear and glassy, a note that suggested night in a remote place. Then, beneath it, as foundation to it, rose a rustling sound as of a forest of reeds through which a breeze went rhythmically. Into this stole the broken song of a thin instrument with a timbre rustic and antique as the timbre of the oboe, but fainter, frailer. A twang of softly-plucked strings supported its wild and pathetic utterance, and presently the almost stifled throb of a little tomtom that must have been placed at a distance. It was like a beating heart.

The Count and his guests sat listening in silence. Domini began to feel curiously expectant, yet she did not recognise the odd melody. Her sensation was that some other music must be coming which she had heard before, which had moved her deeply at some time in her life. She glanced at the Count and found him looking at her with a whimsical expression, as if he were a kind conspirator whose plot would soon be known.

"What is it?" she asked in a low voice.

He bent towards her.

"Wait!" he whispered. "Listen!"

She saw Androvsky frown. His face was distorted by an expression of pain, and she wondered if he, like some Europeans, found the barbarity of the desert music ugly and even distressing to the nerves. While she wondered a voice began to sing, always accompanied by the four instruments. It was a contralto voice, but sounded like a youth's.

"What is that song?" she asked under her breath. "Surely I must have heard it!"

"You don't know?"

"Wait!"

She searched her heart. It seemed to her that she knew the song. At some period of her life she had certainly been deeply moved by it—but when? where? The voice died away, and was succeeded by a soft chorus singing monotonously:

Then it rose once more in a dreamy and reticent refrain, like the voice of a soul communing with itself in the desert, above the instruments and the murmuring chorus.

"You remember?" whispered the Count.

She moved her head in assent but did not speak. She could not speak. It was the song the Arab had sung as he turned into the shadow of the palm trees, the song of the freed negroes of Touggourt:

Knows what is in my heart."

The priest leaned back in his chair. His dark eyes were cast down, and his thin, sun-browned hands were folded together in a way that suggested prayer. Did this desert song of the black men, children of God like him as their song affirmed, stir his soul to some grave petition that embraced the wants of all humanity?

Androvsky was sitting quite still. He was also looking down and the lids covered his eyes. An expression of pain still lingered on his face, but it was less cruel, no longer tortured, but melancholy. And Domini, as she listened, recalled the strange cry that had risen within her as the Arab disappeared in the sunshine, the cry of the soul in life surrounded by mysteries, by the hands, the footfalls, the voices of hidden things—"What is going to happen to me here?" But that cry had risen in her, found words in her, only when confronted by the desert. Before it had been perhaps hidden in the womb. Only then was it born. And now the days had passed and the nights, and the song brought with it the cry once more, the cry and suddenly something else, another voice that, very far away, seemed to be making answer to it. That answer she could not hear. The words of it were hidden in the womb as, once, the words of her intense question. Only she felt that an answer had been made. The future knew, and had begun to try to tell her. She was on the very edge of knowledge while she listened, but she could not step into the marvellous land.

Presently Count Anteoni spoke to the priest.

"You have heard this song, no doubt, Father?"

Father Roubier shook his head.

"I don't think so, but I can never remember the Arab music"

"Perhaps you dislike it?"

"No, no. It is ugly in a way, but there seems a great deal of meaning in it. In this song especially there is—one might almost call it beauty."

"Wonderful beauty," Domini said in a low voice, still listening to the song.

"The words are beautiful," said the Count, this time addressing himself to Androvsky. "I don't know them all, but they begin like this:

The fish dies in the air,

And I die in the dunes of the desert sand

For my love that is deep and sad.'

And when the chorus sounds, as now"—and he made a gesture toward the inner room, in which the low murmur of " Wurra-Wurra" rose again, "the singer reiterates always the same refrain:

Knows what is in my heart."

Almost as he spoke the contralto voice began to sing the refrain. Androvsky turned pale. There were drops of sweat on his forehead. He lifted his glass of wine to his lips and his hand trembled so that some of the wine was spilt upon the tablecloth. And, as once before, Domini felt that what moved her deeply moved him even more deeply, whether in the same way or differently she could not tell. The image of the taper and the torch recurred to her mind. She saw Androvsky with fire round about him. The violence of this man surely resembled the violence of Africa. There was something terrible about it, yet also something noble, for it suggested a male power, which might make for either good or evil, but which had nothing to do with littleness. For a moment Count Anteoni and the priest were dwarfed, as if they had come into the presence of a giant.

The Arabs handed round fruit. And now the song died softly away. Only the instruments went on playing. The distant tomtom was surely the beating of that heart into whose mysteries no other human heart could look. Its reiterated and dim throbbing affected Domini almost terribly. She was relieved, yet regretful, when at length it ceased.

"Shall we go into the ante-room?" the Count said. "Coffee will be brought there."

"Oh, but—don't let us see them!" Domini exclaimed.

"The musicians?"

She nodded.

"You would rather not hear any more music?"

"If you don't mind!"

He gave an order in Arabic. One of the servants slipped away and returned almost immediately.

"Now we can go," the Count said. "They have vanished."

The priest sighed. It was evident that the music had moved him too. As they got up he said:

"Yes, there was beauty in that song and something more. Some of these desert poets can teach us to think."

"A dangerous lesson, perhaps," said the Count. "What do you say, Monsieur Androvsky?"

Androvsky was on his feet. His eyes were turned toward the door through which the sound of the music had come.

"I!" he answered. "I—Monsieur, I am afraid that to me this music means very little. I cannot judge of it."

"But the words?" asked the Count with a certain pressure.

"They do not seem to me to suggest much more than the music."

The Count said no more. As she went into the outer room Domini felt angry, as she had felt angry in the garden at Sidi-Zerzour when Androvsky said:

"These native women do not interest me. I see nothing attractive in them."

For now, as then, she knew that he had lied.

CHAPTER XI

Domini came into the ante-room alone. The three men had paused for a moment behind her, and the sound of a match struck reached her ears as she went listlessly forward to the door which was open to the broad garden path, and stood looking out into the sunshine. Butterflies were flitting here and there through the riot of gold, and she heard faint bird-notes from the shadows of the trees, echoed by the more distant twitter of Larbi's flute. On the left, between the palms, she caught glimpses of the desert and of the hard and brilliant mountains, and, as she stood there, she remembered her sensations on first entering the garden and how soon she had learned to love it. It had always seemed to her a sunny paradise of peace until this moment. But now she felt as if she were compassed about by clouds.

The vagrant movement of the butterflies irritated her eyes, the distant sound of the flute distressed her ears, and all the peace had gone. Once again this man destroyed the spell Nature had cast upon her. Because she knew that he had lied, her joy in the garden, her deeper joy in the desert that embraced it, were stricken. Yet why should he not lie? Which of us does not lie about his feelings? Has reserve no right to armour?

She heard her companions entering the room and turned round. At that moment her heart was swept by an emotion almost of hatred to Androvsky. Because of it she smiled. A forced gaiety dawned in her. She sat down on one of the low divans, and, as she asked Count Anteoni for a cigarette and lit it, she thought, "How shall I punish him?" That lie, not even told to her and about so slight a matter, seemed to her an attack which she resented and must return. Not for a moment did she ask herself if she were reasonable. A voice within her said, "I will not be lied to, I will not even bear a lie told to another in my presence by this man." And the voice was imperious.

Count Anteoni remained beside her, smoking a cigar. Father Roubier took a seat by the little table in front of her. But Androvsky went over to the door she had just left, and stood, as she had, looking out into the sunshine. Bous-Bous followed him, and snuffed affectionately round his feet, trying to gain his attention.

"My little dog seems very fond of your friend," the priest said to Domini.

"My friend!"

"Monsieur Androvsky."

She lowered her voice.

"He is only a travelling acquaintance. I know nothing of him."

The priest looked gently surprised and Count Anteoni blew forth a fragrant cloud of smoke.

"He seems a remarkable man," the priest said mildly.

"Do you think so?"

She began to speak to Count Anteoni about some absurdity of Batouch, forcing her mind into a light and frivolous mood, and he echoed her tone with a clever obedience for which secretly she blessed him. In a moment they were laughing together with apparent merriment, and Father Roubier smiled innocently at their light-heartedness, believing in it sincerely. But Androvsky suddenly turned around with a dark and morose countenance.

"Come in out of the sunshine," said the Count. "It is too strong. Try this chair. Coffee will be—ah, here it is!"

Two servants appeared, carrying it.

"Thank you, Monsieur," Androvsky said with reluctant courtesy.

He came towards them with determination and sat down, drawing forward his chair till he was facing Domini. Directly he was quiet Bous-Bous sprang upon his knee and lay down hastily, blinking his eyes, which were almost concealed by hair, and heaving a sigh which made the priest look kindly at him, even while he said deprecatingly:

"Bous-Bous! Bous-Bous! Little rascal, little pig—down, down!"

"Oh, leave him, Monsieur!" muttered Androvsky. "It's all the same to me."

"He really has no shame where his heart is concerned."

"Arab!" said the Count. "He has learnt it in Beni-Mora."

"Perhaps he has taken lessons from Larbi," said Domini. "Hark! He is playing to-day. For whom?"

"I never ask now," said the Count. "The name changes so often."

"Constancy is not an Arab fault?" Domini asked.

"You say 'fault,' Madame," interposed the priest.

"Yes, Father," she returned with a light touch of conscious cynicism. "Surely in this world that which is apt to bring inevitable misery with it must be accounted a fault."

"But can constancy do that?"

"Don't you think so, into a world of ceaseless change?"

"Then how shall we reckon truth in a world of lies?" asked the Count. "Is that a fault, too?"

"Ask Monsieur Androvsky," said Domini, quickly.

"I obey," said the Count, looking over at his guest.

"Ah, but I am sure I know," Domini added. "I am sure you think truth a thing we should all avoid in such a world as this. Don't you, Monsieur?"

"If you are sure, Madame, why ask me?" Androvsky replied.

There was in his voice a sound that was startling. Suddenly the priest reached out his hand and lifted Bous-Bous on to his knee, and Count Anteoni very lightly and indifferently interposed.

"Truth-telling among Arabs becomes a dire necessity to Europeans. One cannot out-lie them, and it doesn't pay to run second to Orientals. So one learns, with tears, to be sincere. Father Roubier is shocked by my apologia for my own blatant truthfulness."

The priest laughed.

"I live so little in what is called 'the world' that I'm afraid I'm very ready to take drollery for a serious expression of opinion."

He stroked Bous-Bous's white back, and added, with a simple geniality that seemed to spring rather from a desire to be kind than from any temperamental source:

"But I hope I shall always be able to enjoy innocent fun."

As he spoke his eyes rested on Androvsky's face, and suddenly he looked grave and put Bous-Bous gently down on the floor.

"I'm afraid I must be going," he said.

"Already?" said his host.

"I dare not allow myself too much idleness. If once I began to be idle in this climate I should become like an Arab and do nothing all day but sit in the sun."

"As I do. Father, we meet very seldom, but whenever we do I feel myself a cumberer of the earth."

Domini had never before heard him speak with such humbleness. The priest flushed like a boy.

"We each serve in our own way," he said quickly. "The Arab who sits all day in the sun may be heard as a song of praise where He is."

And then he took his leave. This time he did not extend his hand to Androvsky, but only bowed to him, lifting his white helmet. As he went away in the sun with Bous-Bous the three he had left followed him with their eyes. For Androvsky had turned his chair sideways, as if involuntarily.

"I shall learn to love Father Roubier," Domini said.

Androvsky moved his seat round again till his back was to the garden, and placed his broad hands palm downward on his knees.

"Yes?" said the Count.

"He is so transparently good, and he bears his great disappointment so beautifully."

"What great disappointment?"

"He longed to become a monk."

Androvsky got up from his seat and walked back to the garden doorway. His restless demeanour and lowering expression destroyed all sense of calm and leisure. Count Anteoni looked after him, and then at Domini, with a sort of playful surprise. He was going to speak, but before the words came Smain appeared, carrying reverently a large envelope covered with Arab writing.

"Will you excuse me for a moment?" the Count said.

"Of course."

He took the letter, and at once a vivid expression of excitement shone in his eyes. When he had read it there was a glow upon his face as if the flames of a fire played over it.

"Miss Enfilden," he said, "will you think me very discourteous if I leave you for a moment? The messenger who brought this has come from far and starts to-day on his return journey. He has come out of the south, three hundred kilometres away, from Beni-Hassan, a sacred village—a sacred village."

He repeated the last words, lowering his voice.

"Of course go and see him."

"And you?"

He glanced towards Androvsky, who was standing with his back to them.

"Won't you show Monsieur Androvsky the garden?"

Hearing his name Androvsky turned, and the Count at once made his excuses to him and followed Smain towards the garden gate, carrying the letter that had come from Beni-Hassan in his hand.

When he had gone Domini remained on the divan, and Androvsky by the door, with his eyes on the ground. She took another cigarette from the box on the table beside her, struck a match and lit it carefully. Then she said:

"Do you care to see the garden?"

She spoke indifferently, coldly. The desire to show her Paradise to him had died away, but the parting words of the Count prompted the question, and so she put it as to a stranger.

"Thank you, Madame—yes," he replied, as if with an effort.

She got up, and they went out together on to the broad walk.

"Which way do you want to go?" she asked.

She saw him glance at her quickly, with anxiety in his eyes.

"You know best where we should go, Madame."

"I daresay you won't care about it. Probably you are not interested in gardens. It does not matter really which path we take. They are all very much alike."

"I am sure they are all very beautiful."

Suddenly he had become humble, anxious to please her. But now the violent contrasts in him, unlike the violent contrasts of nature in this land, exasperated her. She longed to be left alone. She felt ashamed of Androvsky, and also of herself; she condemned herself bitterly for the interest she had taken in him, for her desire to put some pleasure into a life she had deemed sad, for her curiosity about him, for her wish to share joy with him. She laughed at herself secretly for what she now called her folly in having connected him imaginatively with the desert, whereas in reality he made the desert, as everything he approached, lose in beauty and wonder. His was a destructive personality. She knew it now. Why had she not realised it before? He was a man to put gall in the cup of pleasure, to create uneasiness, self-consciousness, constraint round about him, to call up spectres at the banquet of life. Well, in the future she could avoid him. After to-day she need never have any more intercourse with him. With that thought, that interior sense of her perfect freedom in regard to this man, an abrupt, but always cold, content came to her, putting him a long way off where surely all that he thought and did was entirely indifferent to her.

"Come along then," she said. "We'll go this way."

And she turned down an alley which led towards the home of the purple dog. She did not know at the moment that anything had influenced her to choose that particular path, but very soon the sound of Larbi's flute grew louder, and she guessed that in reality the music had attracted her. Androvsky walked beside her without a word. She felt that he was not looking about him, not noticing anything, and all at once she stopped decisively.

"Why should we take all this trouble?" she said bluntly. "I hate pretence and I thought I had travelled far away from it. But we are both pretending."

"Pretending, Madame?" he said in a startled voice.

"Yes. I that I want to show you this garden, you that you want to see it. I no longer wish to show it to you, and you have never wished to see it. Let us cease to pretend. It is all my fault. I bothered you to come here when you didn't want to come. You have taught me a lesson. I was inclined to condemn you for it, to be angry with you. But why should I be? You were quite right. Freedom is my fetish. I set you free, Monsieur Androvsky. Good-bye."

As she spoke she felt that the air was clearing, the clouds were flying. Constraint at least was at an end. And she had really the sensation of setting a captive at liberty. She turned to leave him, but he said:

"Please, stop, Madame."

"Why?"

"You have made a mistake."

"In what?"

"I do want to see this garden."

"Really? Well, then, you can wander through it."

"I do not wish to see it alone."

"Larbi shall guide you. For half a franc he will gladly give up his serenading."

"Madame, if you will not show me the garden I will not see it at all. I will go now and will never come into it again. I do not pretend."

"Ah!" she said, and her voice was quite changed. "But you do worse."

"Worse!"

"Yes. You lie in the face of Africa."

She did not wish or mean to say it, and yet she had to say it. She knew it was monstrous that she should speak thus to him. What had his lies to do with her? She had been told a thousand, had heard a thousand told to others. Her life had been passed in a world of which the words of the Psalmist, though uttered in haste, are a clear-cut description. And she had not thought she cared. Yet really she must have cared. For, in leaving this world, her soul had, as it were, fetched a long breath. And now, at the hint of a lie, it instinctively recoiled as from a gust of air laden with some poisonous and suffocating vapour.

"Forgive me," she added. "I am a fool. Out here I do love truth."

Androvsky dropped his eyes. His whole body expressed humiliation, and something that suggested to her despair.

"Oh, you must think me mad to speak like this!" she exclaimed. "Of course people must be allowed to arm themselves against the curiosity of others. I know that. The fact is I am under a spell here. I have been living for many, many years in the cold. I have been like a woman in a prison without any light, and—"

"You have been in a prison!" he said, lifting his head and looking at her eagerly.

"I have been living in what is called the great world."

"And you call that a prison?"

"Now that I am living in the greater world, really living at last. I have been in the heart of insincerity, and now I have come into the heart, the fiery heart of sincerity. It's there—there"—she pointed to the desert. "And it has intoxicated me; I think it has made me unreasonable. I expect everyone—not an Arab—to be as it is, and every little thing that isn't quite frank, every pretence, is like a horrible little hand tugging at me, as if trying to take me back to the prison I have left. I think, deep down, I have always loathed lies, but never as I have loathed them since I came here. It seems to me as if only in the desert there is freedom for the body, and only in truth there is freedom for the soul."

She stopped, drew a long breath, and added:

"You must forgive me. I have worried you. I have made you do what you didn't want to do. And then I have attacked you. It is unpardonable."

"Show me the garden, Madame," he said in a very low voice.

Her outburst over, she felt a slight self-consciousness. She wondered what he thought of her and became aware of her unconventionality. His curious and persistent reticence made her frankness the more marked. Yet the painful sensation of oppression and exasperation had passed away from her and she no longer thought of his personality as destructive. In obedience to his last words she walked on, and he kept heavily beside her, till they were in the deep shadows of the closely- growing trees and the spell of the garden began to return upon her, banishing the thought of self.

"Listen!" she said presently.

Larbi's flute was very near.

"He is always playing," she whispered.

"Who is he?"

"One of the gardeners. But he scarcely ever works. He is perpetually in love. That is why he plays."

"Is that a love-tune then?" Androvsky asked.

"Yes. Do you think it sounds like one?"

"How should I know, Madame?"

He stood looking in the direction from which the music came, and now it seemed to hold him fascinated. After his question, which sounded to her almost childlike, and which she did not answer, Domini glanced at his attentive face, to which the green shadows lent a dimness that was mysterious, at his tall figure, which always suggested to her both weariness and strength, and remembered the passionate romance to whose existence she awoke when she first heard Larbi's flute. It was as if a shutter, which had closed a window in the house of life, had been suddenly drawn away, giving to her eyes the horizon of a new world. Was that shutter now drawn back for him? No doubt the supposition was absurd. Men of his emotional and virile type have travelled far in that world, to her mysterious, ere they reach his length of years. What was extraordinary to her, in the thought of it alone, was doubtless quite ordinary to him, translated into act. Not ignorant, she was nevertheless a perfectly innocent woman, but her knowledge told her that no man of Androvsky's strength, power and passion is innocent at Androvsky's age. Yet his last dropped-out question was very deceptive. It had sounded absolutely natural and might have come from a boy's pure lips. Again he made her wonder.

There was a garden bench close to where they were standing. "If you like to listen for a moment we might sit down," she said.

He started.

"Yes. Thank you."

When they were sitting side by side, closely guarded by the gigantic fig and chestnut trees which grew in this part of the garden, he added:

"Whom does he love?"

"No doubt one of those native women whom you consider utterly without attraction," she answered with a faint touch of malice which made him redden.

"But you come here every day?" he said.

"I!"

"Yes. Has he ever seen you?"

"Larbi? Often. What has that to do with it?"

He did not reply.

Odd and disconnected as Larbi's melodies were, they created an atmosphere of wild tenderness. Spontaneously they bubbled up out of the heart of the Eastern world and, when the player was invisible as now, suggested an ebon faun couched in hot sand at the foot of a palm tree and making music to listening sunbeams and amorous spirits of the waste.

"Do you like it?" she said presently in an under voice.

"Yes, Madame. And you?"

"I love it, but not as I love the song of the freed negroes. That is a song of all the secrets of humanity and of the desert too. And it does not try to tell them. It only says that they exist and that God knows them. But, I remember, you do not like that song."

"Madame," he answered slowly, and as if he were choosing his words, "I see that you understood. The song did move me though I said not. But no, I do not like it."

"Do you care to tell me why?"

"Such a song as that seems to me an—it is like an intrusion. There are things that should be let alone. There are dark places that should be left dark."

"You mean that all human beings hold within them secrets, and that no allusion even should ever be made to those secrets?"

"Yes."

"I understand."

After a pause he said, anxiously, she thought:

"Am I right, Madame, or is my thought ridiculous?"

He asked it so simply that she felt touched.

"I'm sure you could never be ridiculous," she said quickly. "And perhaps you are right. I don't know. That song makes me think and feel, and so I love it. Perhaps if you heard it alone—"

"Then I should hate it," he interposed.

His voice was like an uncontrolled inner voice speaking.

"And not thought and feeling—" she began.

But he interrupted her.

"They make all the misery that exists in the world."

"And all the happiness."

"Do they?"

"They must."

"Then you want to think deeply, to feel deeply?"

"Yes. I would rather be the central figure of a world-tragedy than die without having felt to the uttermost, even if it were sorrow. My whole nature revolts against the idea of being able to feel little or nothing really. It seems to me that when we begin to feel acutely we begin to grow, like the palm tree rising towards the African sun."