|

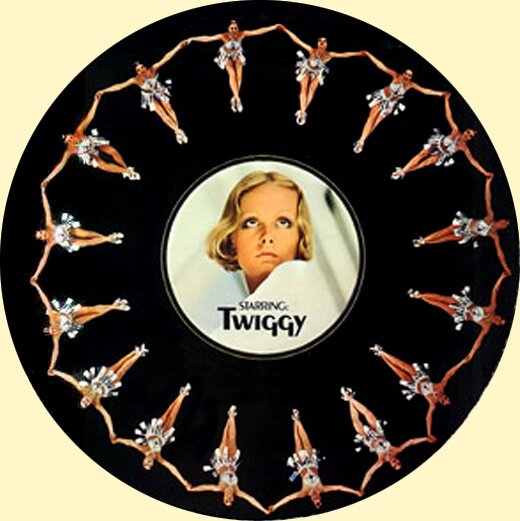

December 02, 2006 The 3 Ages of My Silent Cinema Journey Part Two: The Age of Discovery Sometime around the late 1960s a renaissance of the Silent Cinema began to emerge. It appeared as though the vestiges of a postwar sense of complacency were rapidly being replaced by a new awareness. And an appreciation of the esoteric was one of the fortuitous byproducts of this broadening perspective. The result was a mix of nostalgia and modernism, and somewhere on this eclectic palette was a place for the silent film. This meant that silent films were finally being rediscovered. People were once again watching Keaton, Chaplin and Lloyd. And they weren't just old people either. The films were being shown at college campuses. Audiences were no longer laughing at the perceived primitive nature of the films—they were laughing with them. This trend was reflected in the great mirror of popular culture, Hollywood, which began making what I like to call retro pictures. These were period films imbued with the idyllic cinematic ambience of the twenties and thirties. Hollywood began viewing silents from the perspective of THE BOY FRIEND (which was actually filmed in England) rather than that of SINGIN' IN THE RAIN. Even as I look back on this it still seems too good to be true. And you know what? I think it very well might have been too good to be true when I consider the direction this trend ultimately took. I can recall when all of this began to take place. And whenever I think of the Broadway revival of NO, NO, NANETTE or THE BOY FRIEND (1971) today, I remember the new trend toward the silents occurring in the springtime—but in reality I believe I first received the news in the month of February. Twiggy, who was featured in THE BOY FRIEND, immediately became my favorite contemporary film star. I had known her as a very famous fashion model whom I had been fond of in the sixties but now I saw her in an entirely different light. Twiggy epitomized the new movement in filmdom, for me at least. It was a movement in which contemporary films gleamed with the refreshing artistic aura of the glorious silents and early talkies. It seemed as though the flat black & white and even flatter color of the sixties' films had been supplanted by shimmering shades of nitrate. And we could almost feel once more the soft spray of mist on our faces while watching a Busby Berkeley type number recreated on the big screen. The only palpable difference from the original experience was the zoom-in, which led not to Ruby Keeler but rather to her latest incarnation—a beautiful young woman named Twiggy.

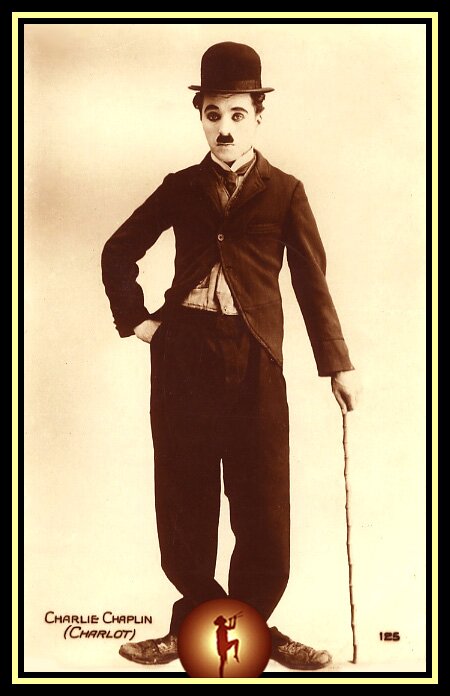

Twiggy in THE BOY FRIEND—The beginning of an era.Showgirls, spectacle and the Charleston were once again larger than life as the shadows of a half-century old dream rhythmically splashed across the movie screens in our towns and neighborhoods. I was a bit awestruck by all of this. Prior to THE BOY FRIEND I had only known contemporary films by their reputation. And I had the impression they were all about people taking off their clothes, smoking marijuana and protesting the Vietnam War. I didn't disagree with their cause but their modes of expression left something to be desired. Finally all of that was changing as a new generation witnessed the return of the glory of Hollywood that some of us had only read about. Silent movie posters were reprinted and there was a nice selection of these - Pickford, Valentino, Chaplin, etc. - if only I had more money in those days! Right around that time public television was born and we finally had an intellectually stimulating alternative to the networks. I immediately became a Public TV fan. Not only did they air programs like MASTERPIECE THEATER but they were showing Chaplin's Mutual shorts in the afternoons. I would try to get home from school early enough to catch the Chaplin film every day even though I had no control over the speed of my transportation. Man, I enjoyed those Chaplin Mutuals—and I was seeing all of them for the first time. I especially liked THE RINK and after seeing it a few times I got my first pair of roller skates. I wanted to learn to skate just as skillfully as Charlie skated, which turned out to be far more difficult than it looked. This was before roller skating came back into vogue in the late seventies and early eighties. I was drawn to the Chaplin films just as Silent Era moviegoers had been drawn to them years earlier—and probably for very much the same reasons. Later on critics would analyze Chaplin and come up with theories about what made him so great. But if they had asked me why I liked him when I first saw the Mutuals I wouldn't have said anything about pathos. I liked the roller-skating and I liked his antics in the pawnshop and on the escalator. I liked his fluid movements in scenes such as the bartending sequence in THE RINK. And I liked Edna Purviance and Eric Campbell. That's all there was to it. In just a few short weeks Edna and Eric became familiar faces and of course I got to know Charlie better than ever before. At that time I got the poster from THE ADVENTURER. I still have that poster today and it can be seen behind me on the comments I record for our Sunrise DVD releases. I always liked it because it not only shows Chaplin but also Edna and Campbell. I thought Eric made an excellent foil and I immediately fell for Edna. As far as I was concerned, she was right up there with Mabel Normand and that was really saying something.

Charlie Chaplin—Afternoon programming at its finest.It was about that time that I also began to learn more about Chaplin and his films through the books that were rapidly becoming available. I got a book describing his films and was even able to get his autobiography in a new paperback edition. It now became easier to find materials about other silent stars as well. And I began to read everything I could get my hands on. I read the autobiographies, the biographies and the film histories. I took notes on index cards, making up a separate set of cards for each star. This of course was long before the days of computers. As the silent stars were being rediscovered I was discovering them for the very first time, even though I already knew them by reputation. I found the stars were not quite the same as they had once seemed to be when I first knew them in the dark age of the sixties. Now they were multidimensional. Silent films, however, were still for the most part extremely difficult to view. I got a film projector and began buying silent films but the cost prevented me from buying very many. I tried to get a job at the cinema when I was eleven years old but they told me they didn't hire children. So I got a job at my school instead. I realized I had to start saving money for college and that didn't leave much to spend on films. So I bought only a couple of films each year and they were shorts at that. The features were far too expensive for me to afford. When I was 16 years old I finally got the job at the cinema—actually my father got it for me. There were four theaters in the complex and they usually showed first-run movies. The first night I worked they were showing THE GODFATHER II, which had been released a few years earlier. I spent part of my first shift walking from one theater to another and watching bits of the films being shown. That evening held a certain wonder for me that I doubt I shall ever experience again in quite the same way—yet I can feel it once more tonight as I sit here writing about it. I was so naive I didn't realize that the Hollywood retro trend wasn't going to last forever. I think it began to fade following the success of STAR WARS (1977), which turned Hollywood away from the past and back to the future. The final 4 years of the retro film now seem but a blur as my education provided me with a rather unpleasant distraction from the movies. And about the time I was regaining consciousness after 4 years of study, the retro quietly died. What had begun with THE BOY FRIEND finally ended with DEAD MEN DON'T WEAR PLAID (1982). So the retro film had lasted about 10 years and in my view the glory of Hollywood was once again a memory rather than a reality. The good news is that the video cassette recorder had arrived and was going to make it big within the next couple of years. The advent of affordable home video was a seminal point in my journey to the heart of the Silent Era, as the VCR opened up a whole new world of silent films for me. I wrote to the major studios requesting they release silents—and two of them did. One replied that they would release about 6 or 7 titles and more would follow, depending on well those sold. None ever followed so that gave me the impression the tapes hadn't sold very well. But at least I had bought them. I soon realized there was no point in waiting for the major companies to release more silents because it apparently wasn't going to happen. But then the public domain companies sprang up. And we had apparently entered a Golden Age of Silent Film—on home video. This was cinematic paradise. I finally began to see a number of silent films for the first time. Although there certainly had been grains of truth in the cardboard cutout images I had once known, the films and the stars were not quite the way I had pictured them. Each film was indeed a revelation. I began to discover that some of the authors whose work had introduced the silents to me had never seen the films they were discussing. That was really an eye-opener. I got to know a couple of college professors who taught film history at nearby universities. They were both very nice and would invite me to sit in on their classes and screenings. Through them I became aware that people were now studying film from various perspectives and viewpoints. Up until that time my only exposure to perspectives other than the traditional historical one had been through the contemporary film magazines, which I read fairly regularly. But I had never really paid much attention to the alternative approaches to film before this time. I must confess that I was not particularly comfortable with the traditional historical perspective, although I certainly did prefer it to the other approaches I was encountering. As much as I loved the silents the historical perspective seemed to be a bit, well, lackluster. I considered the rather prosaic history or some variant thereof and this is how it came across to me: A man named Muybridge way back when took a series of pictures of horses and nudes—but apparently he really liked the nudes because he photographed a lot more of them than he did the horses. And there were also toys based on the persistence of vision. Then came the peep shows—girls dancing, couples kissing, strongmen and the electrocution of an elephant. Why would anyone want to electrocute an elephant and who would want to watch such a thing? Evidently people at that time liked to watch anything that moved. I guess it was a novelty that they were sure to tire of eventually... In 1903 Porter filmed THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY, which was sort of a narrative film and that really caught on. Apparently not very much happened after that because we typically fast forward right up to the Biograph years at this point. D.W. Griffith got pretty good at making films and made THE BIRTH OF A NATION in 1915. The following year he made INTOLERANCE and that one didn't go over very well with audiences. So far the only filmmakers in this story are Porter and Griffith but we do eventually encounter Chaplin, who started out in 1914. Chaplin was "greater" than Keaton, yet Keaton supposedly made one of the greatest films of all time. That was THE GENERAL, which was made in 1927. And that brings us to the year of THE JAZZ SINGER when the talkies arrived and the silent era ended.

May Irwin & John C. Rice in THE KISS (1896).The Historical Perspective—You're more likely to see these two than Colleen Moore or Milton Sills.And there you have it - the history of the silent screen...It isn't quite satisfying, is it? Well I didn't think so either. It isn't the fault of the historians. The verve of the Silent Cinema just seems to get lost in its rather mundane history. However students got more than history in those film courses. They were also given the opportunity to view a number of silent films. We viewed 7TH HEAVEN and THE CHEAT and the class did indeed seem to enjoy them. We viewed INTOLERANCE and it put them to sleep. When we woke one young man up for the intermission he mistakenly thought the film was finally over. You should have seen his look of sleepy surprise when he realized there was yet another 90 minutes or so to go. And a number of students likewise slept through the first half of THE BIRTH OF A NATION—but the second half sure woke them up. We watched some of the VHS tapes released by the public domain companies and everybody seemed to enjoy them. It was at that point I began to question why the so-called quality line classics were putting modern audiences to sleep while the public domain releases were entertaining them. The public domain films in their plain vanilla presentations still contained the essence of the original product. The films retained their vibrancy even though the picture quality was not pristine and the tints were lacking. Everyone seemed to be more interested in viewing these movies than complaining about the fact that old films looked like old films. However the so-called quality line editions seemed to have overlooked something in the process of their restorations. It seemed as though the effort to preserve the entertainment value of the silent film had been given a lesser priority than the effort to venerate the silents as great works of art. And therein lies the problem. Once the silent film had been accepted as a true art form it began to attract those who would haughtily embrace it as a medium too profound to appeal to most members of the general public. The silents had finally earned respect but was it possible we were overdoing it? Did we really have to elevate the status of films such as INTOLERANCE and THE GENERAL to such unrealistic heights? I took a look at that sleepy class and realized we were doing a disservice to the silent film. INTOLERANCE wasn't exactly a popular favorite when it was released in 1916 and it certainly wasn't a popular favorite 8 decades later. In 1916 people were watching Mary Pickford, Marguerite Clark, Doug Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin. That was the reality from a historical perspective. THE GENERAL was entertaining when it was released in 1927 and was still entertaining in the present day. But in the present day it had been transformed into one of the greatest films of all time, which was most certainly a buildup to disappointment. There seemed to have been some rather detrimental side effects to this newfound respect for the silents. And this is what I was referring to above when I wrote that maybe the newfound appreciation of the silents really was too good to be true. For now it had become a status notch for some people to say they appreciated silents. The silent films, or some of them at least, could be considered highbrow. And some people would presumably be willing to suffer through hours of a turgid silent just to have the opportunity to blindly repeat its praise. This, however, was not the cinema that Silent Era audiences had known. They had known the cinema that was entertaining rather than the one that pretended to be so. This new appreciation of the silents problematically allowed room for only the films that somebody somewhere had decided were worthy of restoring and possibly viewing. There was no room for the supposedly "lesser" films of Louise Brooks and a host of others. If you were a Snitz Edwards fan, you were out of luck. In fact you were out of luck if you were a Norma Talmadge fan or even a Colleen Moore fan.

Norma who?Norma Talmadge—evidently unworthy of restoration.There was also no point in restoring films that didn't have pristine picture quality to begin with. Unbelievable as it sounds there are still some people who judge the value of a film by its picture quality rather than its content. That line of reasoning would lead one to conclude that an old episode of THE BRADY BUNCH is more worthy of restoration than a film such as THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME with Lon Chaney. There was yet another side effect. The new resurgence of interest in silents opened wide the figurative floodgates of filmic art appreciation and released a small tsunami of experts upon us. And the existence of experts ultimately led to questions and arguments about all sorts of things. Who invented this or that innovation? What was the "correct" projection speed in those days? Was a certain comedian really serious after all? Was a certain dramatic actor really funny? Was a certain actress born on the 30th or 31st day of the month? Et cetera. Oh man, so many questions. Now we needed people to explain why Chaplin was great. We needed people to identify the classics for us so we wouldn't have to waste time watching the other films, which were less likely to be available anyway. Writers no longer described the silent players in pithy two-word phrases. Now they wrote volumes about how the screen characters of the stars were not actually what they appeared to be. And they told us popular films of the silent era weren't really so great after all while sleepers of the day were actually classics... I would suggest that books such as these are best classified as historical fiction. I came to the conclusion that the historical perspective was considerably less than optimal. And so I tried to identify an alternative. After a considerable amount of effort I gave up my quest for a different approach because I couldn't seem to find one. The historical perspective seemed to be the most accurate in spite of itself and therefore the best perspective from which to study the silent film. But I still wasn't satisfied with it. That was over ten years ago and I did not revisit this issue again until very recently. And only recently have I identified the alternative to the historical perspective that I was seeking a decade ago. What it is might be immediately obvious to some but it took me years to discover—I guess we all find things in our own time. For it is the approach that leads directly to the heart of the Silent Cinema minus all the obstacles and revisions that have been introduced along the way. It is the approach that brings us back full circle to the magic nexus that connected the iconic shadows to the audience of which we are all a part. And it is the approach that ultimately transformed my personal Age of Discovery into what I like to call the Age of Enlightenment, which I will discuss in my next blog. |

|

|