|

March 15, 2007 Cinema Paradiso Not so long ago our towns and neighborhoods had buildings decorated with bright lights, marquees and posters. These establishments were frequently surrounded by crowds of people standing in line, waiting to buy tickets. Upon entry all were greeted by the smell of popcorn. And the darkened chambers within were filled with the sounds of cheers, screams and laughter. Such were the elements of the movie going experience before the days of home video. At that time our afternoons and evenings were colored by both the glamour of the movies and the magic surrounding the place in which they were viewed—the neighborhood cinema. The feelings once evoked from the movie going experience are frequently absent when films are viewed today, as they are usually shown in living rooms rather than cinemas. Cinema Paradiso (1988), however, provides evidence that films can still bring back the feel of going to the movies, even when they are viewed on DVD. This is perhaps accomplished because Paradiso metaphorically takes place in the local cinema that each of us once knew and tells the story of every person who has ever loved the movies. I first saw Cinema Paradiso about 13 years ago in the Garde Theatre in New London, Connecticut. The Garde had a beautiful interior with a huge screen and even a balcony. The night I went to see Paradiso I asked about the theater's history and learned that the first film ever shown at the Garde was The Marriage Clause (1926). The film had starred Billie Dove and was accompanied by a Wurlitzer organ. As I watched the previews that evening I was picturing how Billie must have looked on that large screen back in the Silent Era—and she looked great. Then Cinema Paradiso began. It seemed I was gazing into a great mirror reflecting various long forgotten episodes of my life. Throughout the course of the film I was reminded of the Catholic Church I knew as a child, my deceased father, the job I once had at the local cinema, the man who had been a bit like a second father to me and, most importantly, the girl who was once the girl of my dreams. In spite of all this I didn't fully appreciate the emblematic significance of the film's characters until after the movie had ended. At the beginning of Cinema Paradiso we find the middle-aged filmmaker Salvatore residing in Rome, where he has lived for the past 30 years. When he receives news that a friend from his childhood has died, Salvatore begins to look back upon the events of his life. We then see him as a boy called Toto living in the Sicilian village of Giancaldo.

The Cinema Paradiso LionWhen Salvatore began to reflect upon his life as a child, I was reminded of my childhood as well. As I watched the boy Toto I noticed the actor's close physical resemblance to me when I was his age. And there was more than just a physical resemblance—for just like Toto, I too had loved the movies. Toto's physical features and his love for the movies were not the only factors that brought me back to the days of my childhood, however. I had grown up in an environment where my relatives and their friends all spoke Italian. So the Italian speech in Paradiso was not at all foreign to me. In fact it was quite familiar. My father once told me a story about the Italian immigrants who lived in the neighborhood in which he grew up. He said it was not uncommon to hear a mother refer to her unkempt son as "Charlie Chaplin." The words "Charlie" and "Chaplin" were typically the only words in the sentence that were spoken in English—and the name was pronounced with an Italian accent. I could once again hear my father telling me that story as I watched Paradiso and I smiled at the image it conjured up. I almost expected to hear Toto's mother refer to him as "Charlie Chaplin" but to my dismay she never uttered the famous name. Cinema Paradiso soon transported me back to my early movie going experiences at the Cinema I-II-III in Waterbury, Connecticut. I could remember times when the line of people waiting to buy tickets extended outside the door and around a portion of the Naugatuck Valley Mall in which the Cinema was located. It was astonishing to see so many people waiting in line to see a movie. Sometimes the matinee would sell out before we got to the cashier and we would be able to buy tickets for the next show at the matinee price. Paradiso indeed reminded me of all of that but to a much greater degree it brought back the years I had spent working at the Cinema after it was converted to a Cinema I-II-III-IV. There is a scene in Cinema Paradiso in which Toto is in the projection booth while the projectionist Alfredo is cutting snippets of censored scenes out of a film. Toto asks if he can have the snippets but Alfredo refuses his request, explaining that he has to splice them back into the print later on. Toto then points to a nearby pile of film snippets and asks Alfredo why he didn't splice those back into the prints before shipping them. Alfredo sheepishly explains that it is sometimes too difficult to find the place where the snippets belong and admits that he doesn't really bother to splice them back after all. While watching that scene I saw myself back at the Cinema at the time I worked there. I was standing before the poster cases and became intrigued by a notice printed at the bottom of one of the movie posters on display. According to the notice the poster was to either be returned to the distributor or destroyed after use. Then I noticed that other posters had the same statement printed on them. So I asked the management what they did with the posters after they were finished displaying them. They told me the posters were shipped back to the distributor along with the films. A few years later I stopped by the Cinema one evening just to visit. It was a busy Saturday and one of the girls who worked there was making popcorn in the back room. I had never really liked popping corn myself because it was a rather lonely job. I did, however, enjoy visiting others who were doing the popping—and on this evening I was visiting Cathy. We feasted on popcorn and soda and listened to the radio as Cathy filled bag after bag of popcorn. The huge plastic popcorn bags we used were about the same size as garbage bags. I took periodic trips out to the lobby to get refills on our sodas and to check if the concession stand was in need of more popcorn. In addition to the popcorn machine, the nonperishable supplies for the concession stand were kept in the popcorn room as well. The popcorn and soda cups, napkins and straws were stored in there. The boxes of supplies were always kept in the same places so we could easily locate whatever we needed. That evening I noticed something I had never paid any attention to before. There was a large unmarked box that was seemingly hidden behind the cups and napkins. This newly discovered box looked like it had previously been opened and resealed with masking tape. Cathy and I began to wonder what the mystery box contained and decided to investigate. I had to move a few things out of the way to reach it, and once I managed to get a hold of the box I found it be somewhat heavy. I was then hesitant to open it but Cathy encouraged me to go ahead and break the seal. "I don't think we should be opening this box," I said. "It was in the back like it was meant to be hidden. And we don't even know what might be inside." "That's why we're opening it—to find out what's in there," Cathy explained. "Look, we've got plenty of tape here. We can reseal it later on and nobody will be able to tell we opened it...C'mon. I'm curious now. I want to see what's inside." It was busy out in the lobby that evening. There was a mob of people and the atmosphere was hectic. Somehow all of that made the quiet of the popcorn room that much more exciting, especially considering the discovery we were about to make. In a way it was sort of romantic. I looked up at her once more before opening the box. "If we get in trouble I'm going to say it was your idea." "I'm sure that will get you off the hook," she laughed. "Now stop stalling. Open the box!" I used the little knife we kept in the room for the purpose of opening boxes and carefully broke the seal. I slowly lifted the flaps and looked inside. My eyes widened. "Oh man," I uttered. "Cathy, look at this. I don't believe it!" I felt as though I had just opened a treasure chest. The box was filled with posters and lobby cards. Most of them were brand new—they had never even been displayed. They went all the way back to the early seventies. I began rifling through them, excitedly announcing the names of the films—Jaws, The Godfather, Cabaret, The French Connection, Nashville, Network, Nickelodeon, A Star Is Born... There were advertising materials from all the films I remembered seeing as a child, as well as the films I had missed. I dug deeper and found more—The Sting, Paper Moon, The Great Gatsby, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, That's Entertainment... I couldn't identify any titles that were missing. Everything was there. Everything. Most of the lobby cards were stored in clear plastic wrappers and the sets of lobby cards were complete. I was overwhelmed. "Look at this," I said. "Liza Minnelli, Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Mel Brooks, Madeline Kahn, Robert Redford, Barbara Streisand, Mia Farrow, Goldie Hawn, Gene Wilder, Clint Eastwood... Nobody is missing. There is nothing that is not here! Even the films nobody ever heard of are here!" I looked up at her with wonder in my eyes. Cathy smiled and said, "Rich, I wish I had a camera to capture the look on your face right now." "I wish we had a camera to photograph all of these posters and lobby cards," I said. "This box has been in here all along and we never knew about it. I asked about these posters when I started working here and they told me they sent them all back to the distributor." "You know what I think, Rich?" "What's that?" "I think they were lying to you." I looked up at her. Then we both broke out laughing. The next day we told everybody about our amazing discovery. I told them all about the posters and lobby cards that were hidden away back there. Cathy insisted that the posters and lobby cards were not the best part, however. She kept saying, "The best part was the look on Rich's face when he opened that box. I only wish I had my camera last night." This, of course, was long before the days of cell phones. I had not thought of that incident in years but it came right back to me as I watched Toto asking Alfredo for the film snippets. As Cinema Paradiso progressed I remembered a number of experiences from my days at the Cinema. It was like going back through a long forgotten chapter of my life. And then the evocative Paradiso brought back one of the most impressive Cinema memories of all.

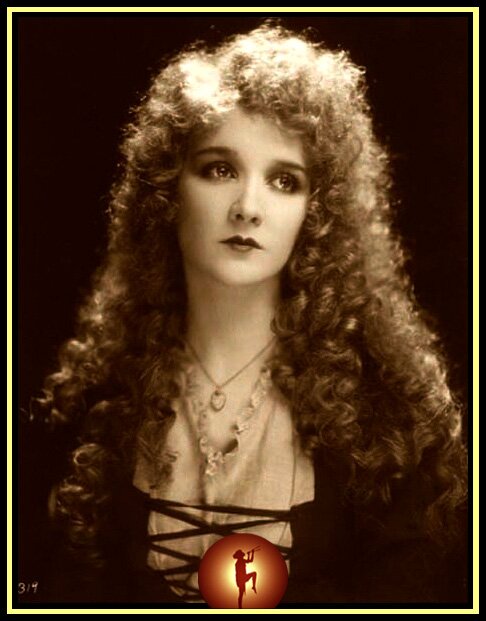

Cinema ParadisoThere is a scene in which the theater is filled to capacity and a large number of people have been turned away. They cry out to Alfredo from the square, begging him to let them see the movie. Toto thinks there is nothing Alfredo can do to please them but Alfredo has a magical surprise in store. He flips a little window on the projector and the moving image is then projected outside onto a wall opposite the theater. The people cheer for Alfredo as they begin to watch the film from the square and Toto is impressed by the magic of the effect. This scene prompted me to once again see myself years earlier when I was working at the Cinema. I had been working there for about 8 months at the time and didn't realize there was much I had not yet seen. It was around the end of the year and the holiday films were showing. The most popular films were always shown in the summer and during the Christmas season. The less popular films and "reruns" were typically shown during the spring and fall. At that time Close Encounters of the Third Kind was playing in our largest theater. I was talking to another usher named Paul, who had been working there for the past couple of years. We had about 15 minutes with nothing to do before Close Encounters broke and he casually asked me if I had ever gone behind any of the screens. I told him that I hadn't. I was a bit incredulous, however, as I never knew such a thing was possible. "You can go behind all of the screens here," he told me. "You didn't know that?" "Are you serious?" I asked with mounting interest. "Sure. You need to use the master key to get in. We've got some time before the show breaks. C'mon, I'll show you." We walked down the aisle of the theater in which Close Encounters of the Third Kind was playing. When we got to the front, the bottom of the screen was well above our heads as it was approximately 10 feet (or roughly three meters) above the floor. We walked through the exit located on the right side of the screen. There was a metal exit door to our right that led to the outdoors. But to our left were about 12 steps that were in total darkness. We used our flashlights to see where we were going as we climbed the stairs. At the top was a locked door. We would have been standing in total darkness if not for the light from our flashlights. Paul produced the master key and slowly opened the door as I peered inside. Once the door was open we were no longer standing in the dark. The room before us was flooded with blue light, which was coming from the movie. The light seemed to be flickering a bit because the image was moving. As I followed Paul into the room he directed my attention to a light switch on the wall. He told me never to turn it on while the movie is showing because the audience would be able to see us if the light were on. This is an experience that every movie lover should have at least once in his or her life. We were standing immediately behind the screen, close enough to touch it. The floor was above the bottom of the projected image such that it was about a quarter of the way up the height of the screen. The picture was in reverse because we were on the backside of the moving image. Remember, this was the last 15 minutes of Close Encounters, which made the effect that much more spectacular. The image was enormous. It was right in front of us such that we could reach out and touch it, and it extended well above our heads. It covered our faces and our bodies. It was on the wall behind us. There was no part of that room that was not covered with the gigantic moving image of Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It felt like we were standing inside of the movie. I noticed that the screen contained rows of tiny holes and when I touched it I found that it was not at all stiff. I was able to depress a tiny area with my finger. When I removed my finger that portion of the screen immediately regained its shape. Paul was clearly enjoying watching my amazement at this incredible site. He told me to look out through the holes in screen. "Look through the holes. You can see the people watching the movie but they can't see you." I moved closer to the screen and prepared to look 'through' the moving image. It almost felt like the image was going to spray me in the face. "Look through it?" I asked, seeking reassurance. Paul laughed. "Go ahead and look through it. It isn't going to hurt you. It's only light." I looked through the holes and could indeed see the people watching the movie. It was so bright where I was standing and yet the audience appeared to be sitting in semidarkness. I could easily make out their faces though. Of course they had no idea I could see them. I was in awe. "I've been working here for months and I never knew about this," I said. "A lot of people don't know about it," said Paul. "Some people work here and then leave without ever finding out about it. I figured you would like to see this though." I thanked him and told him that he had just shown me the most amazing sight I had ever seen at the Cinema. The show was almost ready to break at that point so we left the room and went back out to the lobby. Cinema Paradiso draws attention to the fact that viewing films was once a community experience. I get the same impression when I read some of the comments made by moviegoers in the very early days of the movies. It appears as though early moviegoers were not shy when it came to sharing their views with the rest of the audience. Perhaps many of the people in the audience knew one another, as was probably the case with the myriad neighborhood theaters across the globe. There was a time in my life when I saw almost every film that was released for a period of about 4 to 5 years and in all of that time I only once experienced a true sense of community at the movies. It occurred on a Friday evening about a week before Halloween. I went to see a low budget horror film with a friend and was very surprised to discover that the theater was practically filled to capacity. I spotted another friend in the crowd who was accompanied by some of his friends. He wasn't sitting far from me but he wasn't that close either. The movie began and the viewing experience started out like any other movie going experience. After about half an hour or so, my friend and I decided that we both thought this film was pretty bad—so bad in fact that we began to laugh at how silly the whole thing was. We began laughing at any number of the lines but the audience remained quiet. I suspected the patrons had also decided the film was terrible but were too shy to make their feelings known. I called out to my friend who was sitting a few rows away from me and asked if he was going to demand a refund. Both he and his friends responded. They all agreed the film was bad and began joking about it. We made comments back and forth a few times and that got the figurative ball rolling. Those around us didn't complain about the noise we were making—instead they joined in on the fun. People throughout the audience then began to make jokes in response to the silly lines in the film. And after one person would holler out a comment everybody would laugh. There were some very funny people in the crowd that evening. By the time the film was over there were about 30 of us sharing our comments with the rest of the audience. Between the humorous remarks and the film itself the people were roaring with laughter. Everybody seemed to agree that the movie was terrible but it was obvious that we were all having a great time. After the film ended we were acknowledging each other on our way out of the theater, saying goodnight and agreeing on how bad we thought the movie had been. And I immediately realized that I had just experienced the most enjoyable movie going event I had ever known. Cinema Paradiso was advertised as "a celebration of youth, friendship and the everlasting magic of the movies." I concur and would add that Paradiso celebrated the wonder of the movies as well. When I first viewed the film I questioned how middle-aged Salvatore had ever lost the original wonder of the movie going experience, but as I thought about it I realized that I, too, had lost a great deal of that wonder. I also observed that my view of the world had changed considerably from what it had once been. This especially became clear as I watched the sequence of Cinema Paradiso in which Salvatore first meets Elena. It brought me back to the first time I ever saw Amy. It had happened years earlier in the month of August about 5 o'clock in the afternoon. I saw her standing not too far in the distance with her long reddish blond hair cascading done below her shoulders. I looked at her in wonder and inaudibly uttered the words "Mary Philbin" to myself. I had never seen anyone like her before, at least not in person. And I was certain I had found the sweetest girl in the world. There is a scene in Cinema Paradiso in which Salvatore asks Alfredo for advice about Elena. Their conversation about women in general and Elena in particular brought back a similar conversation I once had with my friend "Crazy" Bob when I first told him about Amy. The age difference between Afredo and Salvatore was approximately the same as the age difference between Bob and me. Bob was sitting on a workbench and I was sitting on a chair, such that I was looking up at him as he spoke. I had told him about Amy's resemblance to Mary Philbin, even though Bob didn't know who Mary Philbin was. Bob insisted that I wasn't seeing things clearly and went on to explain that old-fashioned girls no longer existed. "Once she gets going," Bob said, "every woman has something in her background—a couple of divorces, men she has lived with, a kid or two and anything else she might have picked up and dragged with her along the way. You've got all these starry-eyed notions about Mary somebody or other in the silent movies. And I'm telling you that life isn't like the movies, especially not the old movies. Believe me, I know what I'm talking about." "But Bob, Amy is only 18 years old!" I laughed. "When did she have time for all these different men and children she supposedly has?" "Go ahead and laugh. I don't mean she's got all those things right now. Now she looks like an old movie star that nobody but you ever heard of and you're running toward her in some golden field in slow motion with your arms reaching out in front of you." Bob held his arms out before him and lifted one leg in the air for effect. "But I know what comes next because I've been there." "But you don't understand, Bob. She looks like Mary Philbin. Maybe I need to show you a picture of Mary Philbin and then you'll see what I'm talking about it." "No, you're the one who doesn't understand because you're too young to know any better. I don't care if she looks like Mary Poppins, Marilyn Monroe, or Raquel Welch. It doesn't make any difference. This isn't the movies—this is real life. And this isn't 100 years ago—it's today. Back in your day the movies were silent and the girls were like the old Model T Fords. But in case you haven't noticed, the Model T Fords have been replaced by faster cars and all the old-fashioned girls have likewise been replaced by high speed models." "But you should see Amy," I argued. "With the way she looks, she can't possibly be a high speed model." "Oh boy, you've got a lot to learn. Those are just the genes she's got." "But you don't even know her. How can you say she's high speed?" "I don't need to know her. Every young girl today is a high speed model," Bob pontificated. "One hundred years ago a girl would change her mind in the time it took some guy to figure out how to get all those clothes off of her. But the girls of today are different. Just look how they dress now—they wear next to nothing. You pull two strings and it's all over, baby. Man, you young guys today have got it made and you don't even know what you've got. You're out there looking for some silent movie star when you should be looking for Raquel Welch. And by the way if you ever do come across one who looks like Raquel, send her to me—just don't tell my wife about her." "Okay, if I take your word for it, they're all the same. So what am I supposed to do? Forget all about Amy because you are telling me she is going to sleep with a lot of different men and have their babies?" Bob thought about that for a moment. "Now that I think of it, you're right... I guess you are supposed to do exactly what you're doing. You're young now. Keep on running toward her in that field in slow motion. You'll have to find out for yourself. I just wanted to warn you but you're right—there's really nothing you can do about it. Just remember what I've told you later on." As I was preparing my thoughts for this blog I did an Internet search for Amy. I didn't know if I would be able to find her because she might have gotten married and changed her surname. I did find her, however. I even found a short biography about her that was written a couple of years ago. I discovered that my friend Bob was correct about everything he predicted. I almost regret that I looked for the information because I really prefer the ideal to the reality. In my memory, however, I can still see her exactly as she once looked, just as if her image had been preserved on a pristine 35-millimeter film. And I'll always remember her that way.

Mary PhilbinShortly after viewing Cinema Paradiso in 1994 I drove to Waterbury to visit the Cinema where I had once worked. It took me about 3 hours to get there. When I arrived I discovered the Naugatuck Valley Mall that housed the Cinema was still open but the Cinema itself was closed. Pieces of tarp were crudely hung over the inside of the gate making it nearly impossible to see the area that was once the lobby. I looked through one of the openings between the sections of canvas to get a glimpse of the interior. It appeared as though the theater had been completely gutted. It gave me an empty feeling inside. When I turned around and walked away I realized that was probably the last time I would ever see the Cinema where I had spent so many happy hours—and that indeed turned out to be the case. While preparing my remarks for this blog I did an Internet search to find out if the Naugatuck Valley Mall is still standing today and discovered that it has been gone since 1999. I found a scan of a photograph that was taken shortly after the Mall was demolished. I could still recognize the roads that had once run along two sides of the Mall but there was nothing but dirt where the Mall once stood. I could identify the general area where the Cinema had been located but it looked like an unpaved parking lot in the photo. I read the short article accompanying the scan and discovered that a Wal-mart now occupies the space. I almost can't even picture that, mostly because I don't want to. At the beginning of this blog I wrote that Cinema Paradiso tells the story of every person who ever loved the movies. Once it becomes clear that Toto represents the moviegoer, it follows that Alfredo's character is the personification of the cinema itself. And Cinema Paradiso is a film about the relationship between the two. The significance of Alfredo's character is implied throughout the film. Note that the Cinema Paradiso is demolished upon Alfredo's death, such that both Alfredo and the Cinema depart simultaneously. We see a similar connection early in the film when Toto's mother complains about her son's love for the movies. She says all she ever hears about is "movies and Alfredo—Alfredo and movies." It is almost as though the two are interchangeable. Alfredo was not really a viewer of movies; rather he was a provider of them. This is underscored by the loss of his eyesight, which made him incapable of viewing the films. It is also interesting to note that Alfredo not only showed the films but also spoke the language of the cinema, as he frequently quoted lines from the movies when talking to Toto. At the end of the film Alfredo leaves a gift for Toto that represents the very thing he had given to him during Toto's youth. And it is the same thing all of us are left with after the cinemas in our towns and neighborhoods have been demolished. I believe Alfredo's gift leads Toto to the realization that he is still able to experience the everlasting wonder of the cinema he once knew at the Cinema Paradiso. And with that in mind I have something for you now—simply click on the appropriate link below this paragraph. For as I mentioned above, Toto represents us all, and each one of us is perhaps still capable of experiencing what we, too, once enjoyed at the local Cinema Paradiso—the magic of the movies. * Windows Media Clip (17.3 MB, 9 min. 28 sec.) - PC Users Quicktime Clip (64.5 MB, 9 min. 28 sec.) - Macintosh Users |

|

|